A major new study by researchers at Harvard Medical School and Rush University suggests that lithium—a mineral long used to treat mood disorders—may play a vital role in protecting the aging brain from Alzheimer’s disease. Published Wednesday in the journal Nature, the findings show that even small changes in lithium levels can significantly affect brain inflammation, memory, and the buildup of Alzheimer’s disease-related proteins. The discovery could reshape understanding of the disease and guide new approaches to prevention.

Lithium’s Unexpected Role in Brain Health

Although lithium is widely known as a treatment for bipolar disorder, researchers have now identified it as an essential trace element required by the body in small amounts, similar to iron or zinc. In experiments with mice, reducing lithium intake by just 50% led to faster brain aging, increased inflammation, and more severe memory problems.

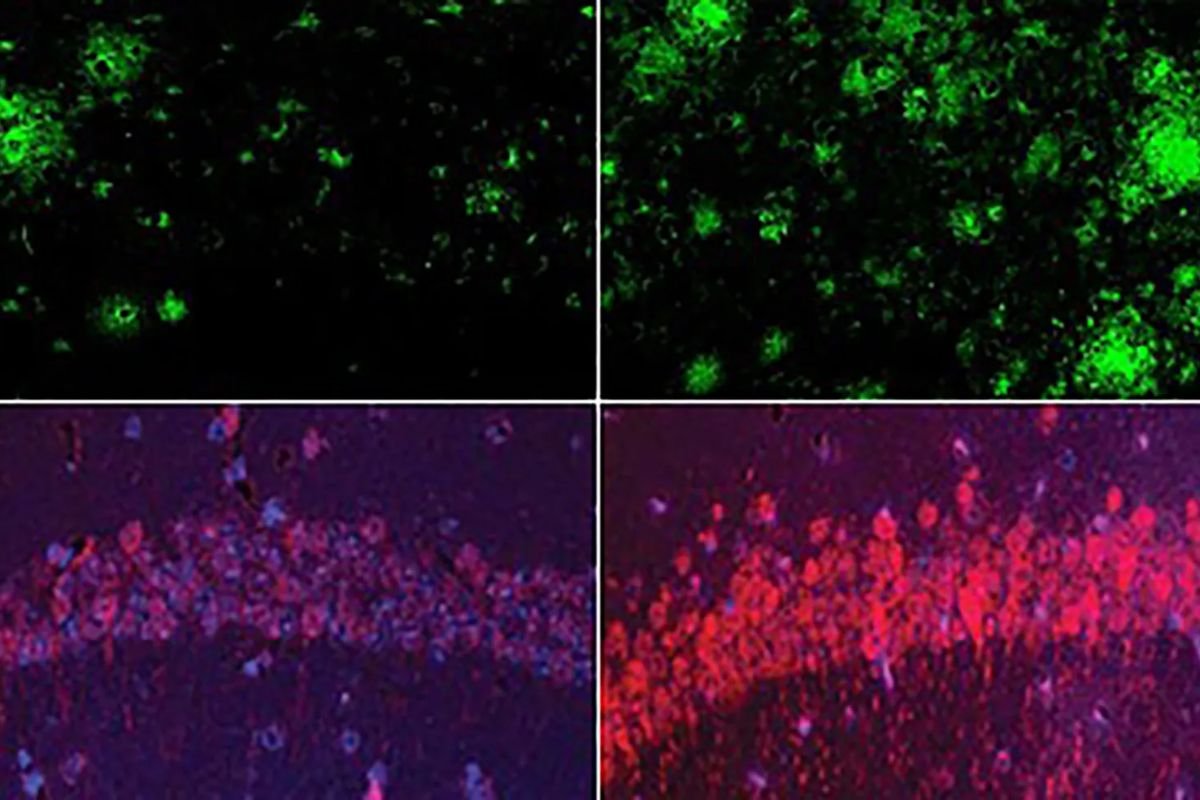

In mice genetically engineered to mimic human Alzheimer’s disease, low-lithium diets caused a faster buildup of beta amyloid plaques and tau tangles—protein deposits strongly linked to the disease. By contrast, maintaining normal lithium levels slowed these changes. Even more striking, treating mice with lithium orotate, a compound that does not bind to amyloid proteins, reversed many signs of brain damage and restored memory performance.

A New Theory Behind Alzheimer’s Progression

The researchers propose a new explanation for how Alzheimer’s disease develops. Beta amyloid plaques, the sticky proteins that collect in the brain, appear to bind with and trap lithium. This deprives nearby cells—especially microglia, which are responsible for clearing waste—of the lithium they need to function properly. As microglia weaken, the brain becomes less able to clear harmful plaques, triggering a damaging cycle.

To test the relevance of these findings in humans, scientists examined brain and blood samples from people with and without Alzheimer’s. They consistently found lower lithium levels in those with memory loss or cognitive decline. These results held across samples from several U.S. brain banks.

Future Possibilities, But No DIY Treatment Yet

While the study offers promising new insight, experts caution against rushing to take lithium supplements. The doses used in this research were about 1,000 times lower than those prescribed for psychiatric conditions. Higher doses, if misused, can cause serious side effects, including thyroid and kidney damage.

“The lithium treatment data we have is in mice, and it needs to be replicated in humans,” said Dr. Bruce Yankner, senior author of the study. He emphasized that clinical trials are necessary to determine safe and effective dosages for people. The National Institutes of Health was the primary funder of the research.

This study adds weight to earlier findings from population studies in Denmark and the UK, which suggested that people exposed to more lithium, through drinking water or prescriptions, had lower dementia rates. It also suggests that some of the benefits of healthy diets may come from lithium-rich foods like leafy greens, legumes, nuts, and certain spices.

While human trials are still needed, the discovery positions lithium as a potential key player in understanding and eventually preventing Alzheimer’s disease.